Tom Rawlings in Response to Equity in Permanency Planning by International Social Service-USA (ISS-USA)

Over the past few years, many state and tribal child welfare agencies have made great progress placing children with relatives if those children have suffered maltreatment and can’t safely live with a parent. State and federal laws require that agencies make a “diligent search” for relatives of children entering foster care, and the federal Fostering Connections to Success Act of 2008 significantly bolstered those search requirements. Nationally, about a third of children in foster care are now placed with relatives, a significant increase from a decade ago. Thousands of children have made the transition from relative foster care to permanent kinship care.

When I talk with child welfare case managers, it’s clear they are now getting better guidance and assistance on searching for relatives, getting home studies completed, and finalizing those relative placements here in the U.S. That’s the case even when the relative lives out of state and the agency has to go through the sometimes complex process required by the Interstate Compact on the Placement of Children.

There is one glaring gap in this family-finding and family-placement work, however, and it involves children who have relatives or parents living in another country. Often these children are US citizens of immigrant parents. If a parent in the United States is unable to care for the child, there may be a parent back in the home country who wants his or her child back. If not, there may be a Guatemalan tia, a French grand-mère, or a Romanian văr who can give that child a home in his or her native culture. Or there may be a close relative who has moved abroad but who could provide a great home for a child in need of safety and security.

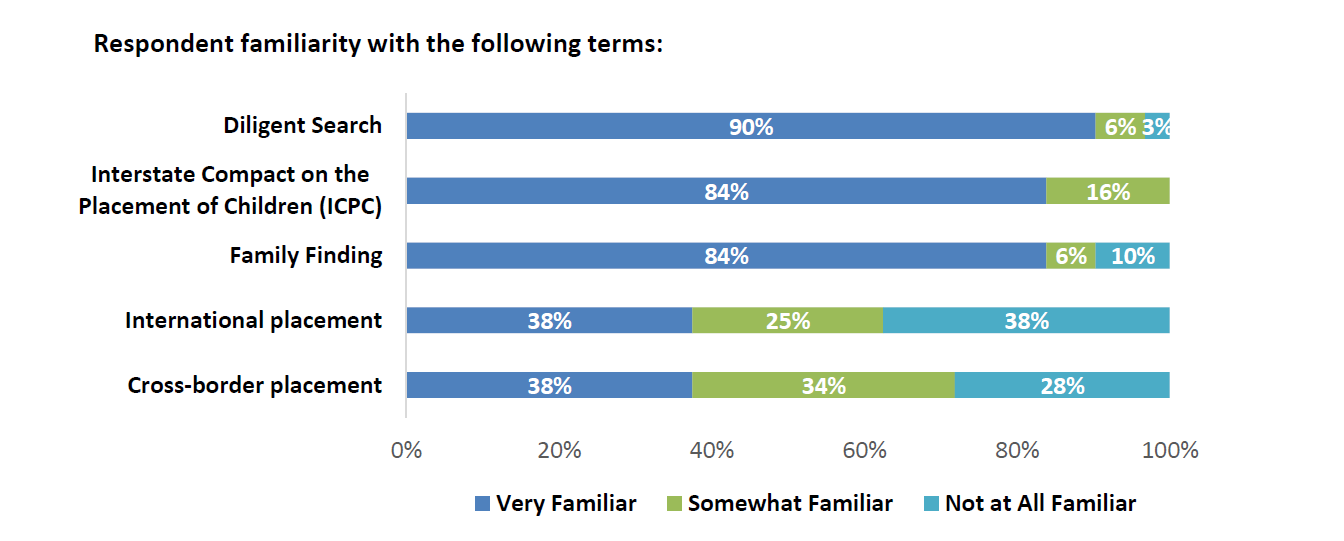

This gap in knowledge is well-demonstrated by a study recently done by International Social Service (ISS-USA) in Baltimore. As part of a global network of experts, ISS-USA has the capacity to conduct home studies for courts and child welfare agencies in almost any country. But as the below graph from the ISS-USA study shows, many child protection officials do not know about the service and do not feel equipped to search for relatives abroad or obtain a home study in another country. While 90% of child welfare professionals responding to the survey are “very familiar” with how to search for domestic relatives and place children within the U.S., up to 40% are not at all familiar with the cross-border placement process.

Adding to the problem, as the study found, is fact that few states have clear policies and practices governing cross-border placements, and only 35 percent of respondents to the ISS-USA survey believed their juvenile or family court would be willing to consider placing a child with a relative abroad.

Having lived abroad with my children for a period, I sometimes thought where they’d live if something happened to their mother and me. I can’t imagine that authorities in the country where we lived would have made any decision other than returning my boys to live with my siblings here in the United States. But each day, child welfare agencies in the U.S. deny to children of immigrants the ability to be reunited with family in their home countries.

For a child victim of maltreatment, the fact that you live in a different country from that of your parent or relatives shouldn’t be used as an excuse to deny you those family bonds. As the report recommends, our federal, state, and tribal child welfare agencies must give cross-border and international relative searches and kinship placements the same priority they give such work on the domestic front.

The ISS-USA study presents a prime opportunity for child welfare agencies in the United States to treat these children equitably and fairly. It’s time that we learn to treat family as family, no matter in which nation they live.

About the Author

Tom Rawlings is an attorney and consultant with Taylor English Duma in Atlanta whose practice focuses on child protection and representation of organizations serving children and youth. His 21-year career in the field includes service as a juvenile court judge, as Georgia’s State Child Advocate, and as Director of Georgia’s Division of Family and Children Services. He often works alongside national and international authorities to protect immigrant children and reunite them with family in their country of origin.